Christmas is barely mentioned in any of Austen’s novels. (Quick—can you think of two places where it is mentioned? Post your answers below!) At first glance, it seems strange that a clergyman’s daughter—one who wrote memorable prayers and was notably pious—would ignore such a major religious holiday in her fiction. A closer examination, however, sheds light on this seemingly puzzling contradiction.

First, we must remember that the Christmas season in Austen’s time was not the celebration we know today. Christmas meant church attendance, good food, and hospitality—not weeks of anticipation or intense emotional focus. Regency England had no Christmas trees, no Christmas cards, and no preoccupation with a certain red-cheeked visitor from the North Pole. Simply put, Christmas did not yet carry the cultural weight it does now.

Second, even if Christmas had packed the same emotional wallop then that it does today, I suspect Austen might still have avoided it. Her novels are marvelous, in part, because they make so much of the ordinary humdrum of daily life. A dance at an assembly creates friction between two unlikely soulmates. Information gleaned from everyday letters fuels hours of speculation. A routine social call is laced with emotional landmines. A walk to Mount Oakham becomes the most portentous moment in a young woman’s life. Austen does not need the drama of Christmas—she supplies the drama herself. A masterful writer, indeed!

Finally, it is worth reminding ourselves that although Austen’s faith was deeply felt, it was also largely contained. She admired the evangelicals of her day but did not emulate them—at least not in her fiction. There is no overt preaching in her novels. Her characters go to church, but we never hear what they listen to or what they sing. Clergymen abound, yet not a single sermon appears on the page. If there is moralizing, it lies instead in moments such as Darcy and his father being praised for their compassion toward the poor, or in the dead silence that follows Fanny Price’s question to her uncle about the slave trade. In Austen’s fictional world, making Christmas the source of dramatic significance would likely feel overdone and out of keeping with the rest of her work.

Given all this, the absence of Christmas from Austen’s novels makes perfect sense.

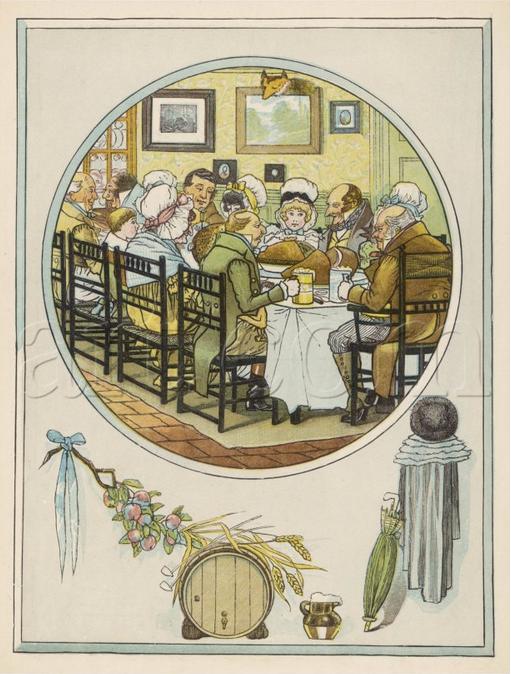

So how might Austen—or her characters—have spent Christmas? Following the conventions of the time, they would likely have attended a church service in the morning and then returned home for a quiet but celebratory meal with their immediate family. The following day, Boxing Day, they would give gifts to their servants and perhaps send gratuities to favored tradesmen. Food or other necessities might be distributed to the poor, and much of the day would be spent visiting from house to house. To me, it sounds like a rather wonderful holiday!

However you choose to spend the day tomorrow, here is a thought Austen herself would surely approve: meaningful change rarely announces itself with garlands and candles. More often, it arrives quietly—on the wings of duty and affection—and leaves us better than it found us.

Have a wonderful and blessed holiday!

For further reading:

Leave a Reply to Regina JeffersCancel reply