Slavery was one of the most contentious issues of Jane Austen’s time. Some scholars claim that she ignored the issue or even accepted the legitimacy of the practice. Others claim that her novel Mansfield Park serves as an anti-slavery tract. For certain, Austen would have tackled the complex issue in a complex way.

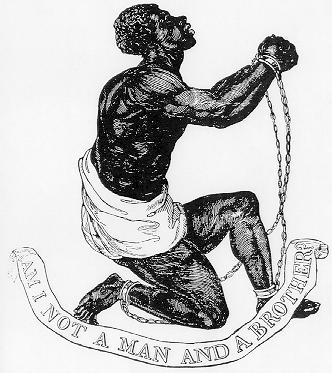

The fight to abolish the slave trade—the buying and selling of slaves—had been raging since 1787, when Thomas Clarkson, who had won an essay contest at Cambridge condemning slavery, helped form the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Another founding member was Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery magnate, who created the official emblem of the group, an image of a chained slave (see image) with the plaintive cry “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?”

Soon after, Clarkson gave William Wilberforce a copy of his pamphlet. Shortly after that came the famous meeting under the oak tree on William Pitt’s estate in which Pitt and William Grenville, two future prime ministers, convinced Wilberforce to take up abolition as his main political cause in the House of Commons. In Pitt’s fabled words, “We were too young to realize that certain things are impossible, so we will do them anyway.”

It was Grenville who shepherded the final bill through after Pitt’s death in 1806. Ironically, Pitt had become a (temporary) opponent to abolition because the cause made it harder for him to keep his pro-war political coalition together against France.

The climactic vote to end the slave trade came in March 1807, when Jane Austen was at the peak of her authorial powers. It took another generation before England abolished slavery entirely—six months after the death of Wilberforce in July 1833. Three days before he died, Wilberforce is said to have been assured of the passage of the bill. The end to slavery in all English possessions was phased in over six years, beginning in 1834, and slave owners received twenty million pounds in recompense. (The period was later shortened to three, and several islands controlled by the East India Company were included.)

Josiah Wedgwood of the famous pottery family was an ardent abolitionist. He created this image as the symbol of the effort to end slavery.

It is not surprising that it took twenty years to end the purchase of human flesh and another twenty-six to end slavery itself. The practice was deeply embedded in the English economy.

In the early years, the focus was to end the misery of the capture, sale, and transport of slaves, though abolitionists assumed the end to slavery would come eventually. There was the hope that, if slave holders could not buy more, they would treat their current slaves better: It was cheaper to buy a new human being than to feed one you had.

Slavery is perniciously difficult to eliminate once it is in place, for free labor has an addictive effect on the beneficiaries. The slave trade represented 5 percent of the British economy, with a slave ship departing England every day. When everything is tallied—manufactured goods, tools, and rum to Africa; slaves to America; rum, sugar, tobacco and cotton to England—the Triangular Trade represented 80 percent of England’s overseas trade. Liverpool and Bristol were the two largest slave-related ports, which gives us the hint that Mrs. Elton’s family was involved in Emma.

Its tentacles stretched far enough to ensnare the Austen family. Mr. Austen’s half-brother, William Hampson, owned a Jamaica plantation, and Jane’s father was also a trustee of a slave plantation in Antigua for a friend, James Nibbs. Nibbs was godfather to Jane’s brother, James. It does not appear that Mr. Austen ever did any work related to the trust.

Aunt Leigh-Perrott was heir to a plantation in Barbados, meaning that any inheritance from that side of the family—which the genteelly poor Austens desired—would have been tainted. The family received none, though, until Aunt Leigh-Perrot’s death in 1836, after slavery itself had been voted out.

What of Jane Austen’s own point of view? We know that her favorite authors opposed slavery, including the poet William Cowper, who penned the famous lines celebrating Lord Mansfield’s freeing of a black slave in England in 1772: “Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs/Receive our air, that moment they are free;/They touch our country, and their shackles fall.”

Jane’s niece Fanny had an anti-slavery story in her diary in 1809; it’s likely her views would have been shaped by Jane, Cassandra, and others of her aunts’ generation. Frank Austen is the only Austen sibling known to have actively denounced slavery during her life. His views likely shaped Jane’s.

In a letter home in 1808, Frank compared the relatively “mild” form of slavery practiced at St. Helena in the eastern Atlantic with the “harshness and despotism” practiced in the West Indies. In St. Helena, a slave owner could not “inflict chastisement” on a “refractory” slave; he must apply to the magistrate for relief. Frank concluded with characteristic honesty:

“This is wholesome regulation as far as it goes, but slavery however it may be modified is still slavery. [No] trace of it should be found … in countries dependent on England, or colonized by her subjects.”

In her letters, Austen indirectly praises Thomas Clarkson by saying she was “as much in love” with author Charles Pasley as she ever was with Clarkson—a likely reference to Clarkson’s book, History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1808).

Mansfield Park has a number of references to slavery, from the title itself—Lord Mansfield having freed the slave Somerset and by extension all slaves in England—to Mrs. Norris, evidently named for a slaver who tormented the abolitionists, particularly Clarkson. Whether the novel itself stands opposed to slavery is a matter of dispute; personally, I believe Austen was too much of an artist to telegraph her own views.

All of these references, however, come after the end to the slave trade in early 1807. Barring the discovery of new family letters, it’s unlikely we’ll know Austen’s true views during the years leading up to 1807. Her beliefs likely evolved along with those of England in general, with little thought early on and a growing realization of the horrors of slavery as opponents brought its true practices into public view.

Given her respect for her older brother, Frank’s ardent opposition to slavery likely galvanized her own opposition as she matured.

There’s poetic justice that the Royal Navy, which had earlier protected slaving ships making the Middle Passage from Africa to the Americas, now enforced the ban on slave traffic. Two generations of Austen men, beginning with Frank and Charles and continuing through their self-named sons, intercepted slavers on the open seas.

And long after Jane’s death, another brother, Henry, attended the first international antislavery convention in London in 1840. Devoney Looser, who uncovered this information, points out that in one generation the family went from indirect beneficiaries of slavery (as all British families were) to being staunchly opposed.

—

My new book, Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction: Six Novels in “a Style Entirely New,” investigates her development as a writer and shows how her innovations as a prose stylist set the course for modern fiction. It is available from Jane Austen Books at a special low price.

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen is also available from Jane Austen Books and Amazon. The trilogy traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions. A “boxed set” that combines all three in an e-book format is also available.

Leave a Reply